|

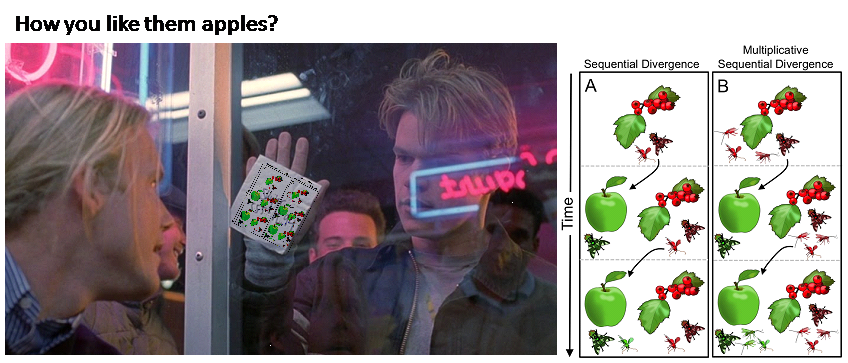

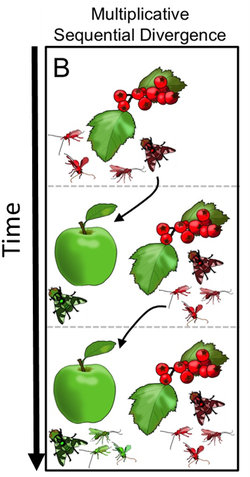

Scene from Goodwill Hunting where Matt Damon boasts of the awesomeness of sequential speciation. What determines species diversity? This is one of the most important questions facing biological sciences. It turns out that species themselves may create new biodiversity. The idea is rather simple: as new species colonize and adapt to new environments, they create new opportunities for other organisms to colonize and adapt, potentially setting off a chain reaction of adaptation events within communities and across ecosystems. The process, referred to as “sequential” or “cascading” divergence, has been hypothesized to help explain a number of biological patterns including periods where there has been an explosion of new species following mass extinctions and the inordinate amount of species diversity found in tropical environments. Do we observe sequential speciation in nature?

If we knew of a plant-feeding insect that recently diverged – split into new species – then we could look to see if their parasitoids have followed, also diverging into new species. Well…about 400 years ago, domesticated apples were introduced from Europe to the United States. These new apples did not go unnoticed by some of the locals. A species of fly that had long been living in the US that fed on the fruits of hawthorn plants (Rhagoletis) started laying eggs in apple fruits, and before long, the species had begun to split into two diverging lineages – one that still fed on the hawthorn plants and another that fed on the newly introduced apples. What kept these diverging flies from merging back into one species? Well, the hawthorn and apple fruits produce different chemical signals (they basically smell different) and the flies evolved to use these differences to find their “favorite” host. Because the flies mate on their host plant, apple-loving flies only mated with apple-loving flies while hawthorn-loving flies only mated with hawthorn-loving flies. Over time, the two forms mated less and less and began to become genetically different. Also, the fruits develop at different times of the year, so the flies had to adjust their internal clocks to match when their food was available. That is they evolved (adapted) to match the timing of their host. Those best synchronized to their host, whether it be apple or hawthorn, had the highest fitness – passing on more descendants with similar traits – until they now not only differ in what smells they like, but when they are flying around looking for mates. Because they began to start mating at different times of the year, those who chose apple became less and less likely to mate with those that stuck with hawthorn. Crazy enough, all of this has actually occurred multiple times in other closely related flies, adapting to other plants, such as blueberries, snowberries and dogwoods. So, did the parasitoids split into new species, like their fly hosts?

The study "Sequential Divergence and the Multiplicative Origin of Community Diversity" published in PNAS can be found at: www.pnas.org/content/112/44/E5980.abstract

2 Comments

|

Authorsmany diverse authors write these articles Archives

April 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed